The collapse of Lehman Brothers occurred just over ten years ago on September 15, 2008. It represented the pinnacle of the financial crisis as it pushed the global financial system to the brink of failure. Throughout the past ten years our Investment Committee has spent many hours reflecting on the crisis, trying to understand what happened and what we can learn from it. Often, the takeaways were things we knew before the Great Recession, but were now reinforced and learned again. Those items, plus a few new ones, are the top five lessons we learned (or re-learned) since Lehman’s collapse.

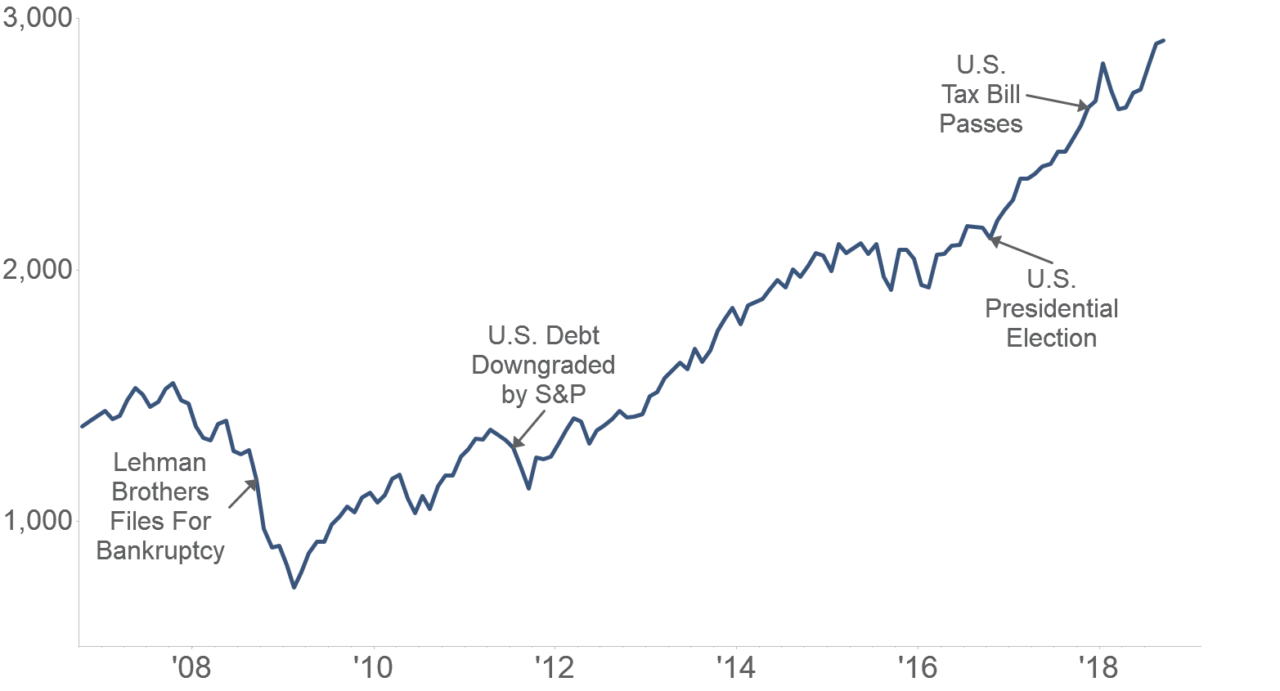

Stock Market Performance

S&P Composite Index

1. It Is Really Hard to Predict a Financial Crisis

In the fall 2006 I attended an investor conference that featured Alan Greenspan, who had completed his service as Chairman of the Federal Reserve earlier that year. The following highlights, which I took directly from my notes that day, provide Mr. Greenspan’s outlook for various areas of the economy at that time:

- The economy is going through a “slow period” which is likely temporary. There will be a weakening in the fourth quarter of 2006, but then the economy will pick up pace.

- Corporate profit margins are strong, and they will continue to strengthen over the next few years, leading to economic health and expansion.

- Overall, “the global economy is in extraordinarily good shape.” It’s not perfect, but it’s pretty good and should continue to be healthy.

- The housing market is in good shape. While house prices have risen quickly, they probably will level off a bit. In response to a question about sub-prime and non-traditional loans and their effects: “subprime loans are only a very small proportion of the mortgage market” and thus, “they shouldn’t be a problem.”

Alan Greenspan was momentously wrong. Embarrassingly wrong. How could the recently retired Chairman of the Federal Reserve have no idea what was about to happen?

To be fair, his views reflected what the vast majority of people thought at the time. At another industry conference one year later in the fall of 2007, the manager of one of the biggest REIT (“real estate investment trust”) funds in the U.S. said that the “subprime loan problem” is overstated and that their fund was bullish on the real estate sector.

It turns out that only a small number of people in 2006 and 2007 surmised that a crisis of historic proportions was on the horizon. Quite simply, relying on experts to correctly predict a bear market or financial crisis is not a good strategy.

Lesson: Profitably predicting a bear market or financial crisis is very difficult. Instead of attempting to time the market, a better practice is to create an all-weather portfolio that will grow in bull markets and provide relative preservation during bear markets.

2. Liquidity Is Key

A key lesson learned by individual investors and institutions alike is that when financial markets are under great stress, there is no substitute for liquidity. In the depths of the Great Recession, assets considered liquid – like municipal bonds and auction-rate preferred securities – could be sold only at discounted prices. Large endowments and foundations experienced liquidity crunches because of their sizeable allocations to illiquid alternative investments, such as private equity, private real estate and hedge funds. Some endowments had to sell their interests in alternatives at deep discounts in the secondary markets. Likewise, many individual investors were forced to sell investment assets at depressed prices because they did not have adequate liquidity heading into the crisis. In 2008 and 2009 there was no substitute for having cash.

Lesson: Our advice to clients is to have cash on hand equal to expected portfolio withdrawals for at least one year, and as much as three years. Having that much liquidity will allow them to ride out much or all of market stress. In addition, it is wise to have part of a portfolio in high-quality fixed income that will act as dry powder during a down equity market (more on this topic below).

3. We Live In a Global, Inter-Connected Economy

When the financial crisis materialized, there was no place to hide. Domestic and international equities, fixed income and alternative investments all lost significant value. Portfolio diversification only goes so far in today’s inter-connected global economy.

Problems in the U.S. created problems for the rest of the world; the saying “when the U.S. sneezes, the globe gets a cold” is apt with respect to the global economy. Similarly, struggles in the rest of the world can create problems within our domestic economy and markets (remember the European Sovereign Debt crisis in 2008-2009). Considering political and economic issues only in the U.S. is simply not broad enough.

Not only did international diversification falter, but in 2008 and 2009 most asset classes fell dramatically and in lockstep. Investors who thought they were well-diversified learned otherwise as they experienced massive declines in much, or all, of the asset classes within their portfolios. Even many hedge fund strategies marketed as being “absolute return funds” or “market neutral” suffered declines in excess of 20%.

The primary type of investment that held its value during the crisis was investment-grade bonds. These bonds – treasuries, agency-backed bonds, and high-quality corporate and municipal bonds – all weathered the storms of the financial crisis relatively well in comparison to the other asset classes.

Lesson: While it makes sense to diversify globally, it is not a panacea when it comes to a financial crisis. Also there is no substitute for having high-quality bonds in a portfolio for purposes of preservation. In a severe bear market or financial crisis, it is likely that most, if not all, risk assets will sell-off together. Maintaining sufficient safe assets in the form of high-quality bonds allows an investor to deploy into other investments that are relatively cheap.

4. You Can’t Plan for Financial Armageddon

In late 2008 and early 2009 there were many economists, bankers and investment managers legitimately afraid that the global financial system was going to fail. I vividly recall a conversation in early 2009 with a New York-based hedge fund manager who had bought farmland in New Jersey as an escape from the city when everything collapsed, which he thought was imminent. Another New York-based investment manager around the same time predicted that the Dow Jones Industrial Average was going to fall to 1,000 (it bottomed at around 6,000). We are fortunate they were wrong!

What would have happened if the global financial system collapsed? We don’t know. It is hard to imagine. The possible outcomes, while varied, likely fall along two lines: (a) much of the system holds together, fiat currencies (the dollar) still have value and eventually the markets recover (which is what happened); or (b) it is Armageddon: sovereign debt defaults, fiat currencies lose most or all of their value, stock exchanges lock up and are closed and panic ensues.

Under scenario (a) it makes sense to have plenty of cash and other assets that will hold value and survive (like high-quality bonds). Under any version of (b), there is nothing you can do to plan financially.

Lesson: In terms of investments, it doesn’t make sense to plan for Armageddon. Instead, we advise clients to plan for a market recovery following a crisis. Survival in the anarchy following a financial system collapse is a different proposition, which is not impacted by portfolio decisions.

5. In the Depths of Bear Markets, Opportunity Abounds

Markets are generally efficient and usually forward-looking, even in the throes of a painful bear market. Yet this fact is often overlooked by the news media who fuel investor fears with negative short-term economic and financial data. Eventually, the investor distress subsides, but before they are comfortable to act, the markets have turned, resulting in investors missing out on dislocations and attractive opportunities. People are understandably reluctant to rush into a burning building, but metaphorically that is what investors need to do to capitalize on various market dislocations.

Generational investment opportunities emerge from times of great stress, and investors must act against their prevailing heuristics and fear gauges to capitalize on them. It is incredibly difficult to do this, but not impossible. Liquidity and financial feasibility are key variables, as is having a systematic process (i.e. behavior-free) for investing and rebalancing.

Lesson: If an investor enters a bear market with adequate liquidity and capital preservation assets, it may be possible to invest in distressed assets that could provide outsized returns.