If you were an adult in the late 1970s, you might remember President Gerald Ford declaring inflation “public enemy number one” and introducing the slogan “Whip Inflation Now” as part of a campaign to fight inflation through grassroots action. The Whip Inflation Now campaign included wearing buttons with “WIN” on them, which seems silly now, but illustrates how much of problem inflation was in the 1970s. Eventually, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker killed inflation in 1982 by raising the Federal Funds Rate to nearly 20% and sending the economy into recession along the way.

The high inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s, and the Fed’s painful actions to quash it, left an indelible mark on our nation’s economic psyche. In the late 1990s, Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Shiller surveyed Americans about their inflation views.[1] One of his questions was, “Do you agree that preventing high inflation is an important national priority, as important as preventing drug abuse or preventing deterioration in the quality of our schools?” Shockingly, 84% of the respondents agreed with this statement. Another 86% reported being angry when they saw higher prices. The respondents viewed inflation as a result of businesses being too greedy, the Fed acting stupidly, and the government spending too much and letting deficit get out of hand.

So, as a society, we have an ingrained antipathy towards inflation. The inflation numbers from recent months are stoking fears that we might be in for a 1970s inflation redux. Indeed, the 7% annualized increase in the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) in December of 2021 is the most inflation we’ve experienced since 1982. This is in stark contrast to the low inflation we’ve experienced for the past few decades. In fact, since the start of the Great Recession, inflation has been running below the Fed’s target, and it has struggled to create inflation.

What is Inflation?

Inflation occurs when a currency loses purchasing power and we experience inflation through rising prices. The most common measure of inflation is CPI which tracks the price changes for a basket of goods and services, divided into eight groups that represent primary consumer needs.

CPI has various flavors, including headline versus core, trimmed vs. untrimmed, with or without seasonal adjustments, and urban or all consumers. Additionally, there are dozens of other inflation statistics such as Personal Consumption Expenditures (the measure favored by the Fed), the Producer Price Index, and the Wholesale Price Index.

While understanding overall price increases in the economy is important, each of us consumes various goods and services in different proportions, so each of us has our own personal inflation rate. If you have a child entering college in the next few years, price increases for education matter a lot, while people with a long commute are more affected by gas prices than someone with a short commute or who takes public transit. So, depending on your spending patterns, you will experience more or less inflation than the economy as a whole.

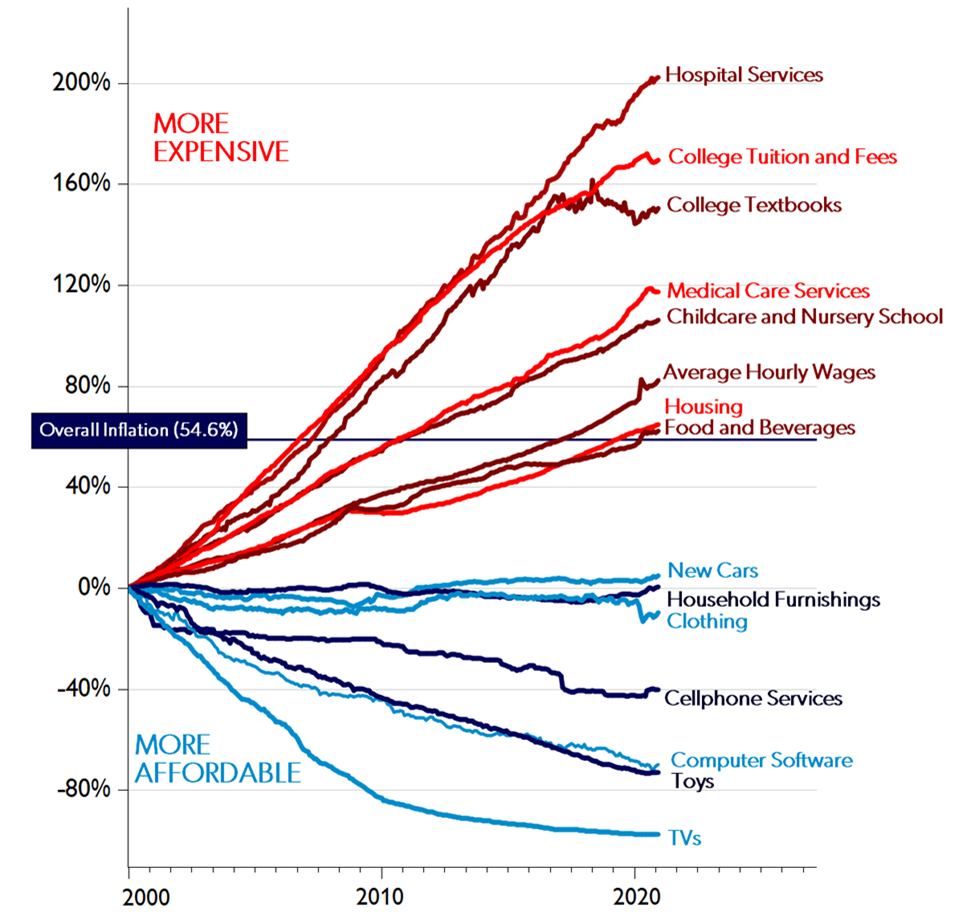

Here’s a great chart showing some of the components of CPI and how they’ve changed over the 20 years ending 2020. You can see that what you typically buy will have a big effect on your personal inflation rate.

Price Changes; January 2000 to December 2020

Selected US Consumer Goods and Services, Wages

What Causes Inflation?

Our economy is unbelievably complex, with millions of businesses selling tens of millions of goods and services to hundreds of millions of consumers. Supply and demand interact to set prices that rise and fall. New technologies, trends, government spending, and pandemics all affect prices. As such, there is no one factor that we can point to and say, “this is what causes inflation.” That being said, the causes of inflation tend to fall within three categories:

- Demand-Pull Inflation | When demand for items outstrips supply, prices rise. Over the past year, we’ve seen this as the pandemic has disrupted supply chains across all sorts of goods. You’ve experienced this if over the past year and a half you’ve tried to buy furniture, a new or used car, or a can of coconut milk (this weekend, I went to three grocery stores, and they were all out). At the same time, demand has risen as consumer spending has rebounded from the depths of Covid. If supply is constrained compared to demand, businesses can and will raise prices, which is inflationary.

- Cost-Push Inflation | This type of inflation results when the costs of inputs increase. Wage increases significantly affect inflation as labor costs constitute over two-thirds of the cost of goods and services in the U.S. If employers have to pay employees more, they will pass these higher costs on to consumers. For reasons not clear to economists, the labor supply has been shrinking as a record number of people have been quitting their jobs. Dubbed “the Great Resignation,” employees leaving their jobs en masse leads to wage growth as employers struggle to fill vacant job positions and have to offer higher wages to retain employees. Rising cost of raw materials and energy also contribute to cost-push inflation.

- Monetary-Induced Inflation | Milton Friedman argued that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” While this statement has proven too strong, the value of money is indeed affected by the supply and demand for that money. Thus, if too much money is pumped into the economy through the Fed’s monetary policy or fiscal spending, the dollar’s value will cheapen, which is the very definition of inflation.

Currently, we are experiencing inflation pressure in all three categories. Demand is outstripping supply as businesses deal with the effects of COVID, wages are increasing, energy prices have soared, and the Fed and Congress have been pumping money into the economy for over a decade.

Why is Inflation A Problem?

I recently read a book about cryptocurrencies that contained a diatribe against inflation. It noted that “inflation is a stealth tax that hits every American” and “the U.S. dollar has lost over 95% of its purchasing power in 100 years.” This is a common view and captures our base aversion to inflation.

Contrary to this view, however, central banks and economists across the globe think that a low to moderate amount of inflation is a sign of a healthy economy. While zero inflation sounds great in theory, it’s not so great in reality. A study by the Brookings Institution concluded that having zero inflation would result in “a continuing loss of 1 to 3 percent of GDP a year, with correspondingly higher unemployment rates.” Here’s why some inflation is desirable:

- As the economy grows, demand for goods and services increases, generating inflation. So, having some inflation is a sign of a healthy economy.

- Inflation is vital to economic growth. When we think prices will be higher in the future, we are encouraged to buy goods and services sooner rather than later. Additionally, inflation is important for employers. According to the Cleveland Fed, an essential benefit of a “small amount of inflation is that it may improve labor market efficiency by reducing the employers’ need to lower workers’ nominal wages when economic conditions are weak. This is what is meant by a modest level of inflation serving to ‘grease the wheels’ of the labor market by facilitating real wage cuts.”

- Deflation, which is the opposite of inflation, can create a crippling feedback loop: if we think prices will be lower in the future, we’ll hold off making purchases, which will cause businesses to reduce prices to spur demand, which causes more deflation, which further incentivizes consumers to delay purchases. Thus, low to moderate inflation is desirable to act as a buffer against deflation. According to the Federal Reserve, “If inflation expectations fall, interest rates would decline too. In turn, there would be less room to cut interest rates to boost employment during an economic downturn. Evidence from around the world suggests that once this problem sets in, it can be very difficult to overcome.”

But like most things, inflation is only good in moderation, and high inflation is problematic:

- If inflation runs too hot, the Fed might raise interest rates which will slow economic growth by increasing business and consumer cost of capital and can even lead to a recession and increases in unemployment.

- Higher prices can lead to essential goods like food or gasoline becoming unaffordable for consumers whose paychecks don’t keep up.

- Higher inflation comes with higher price volatility, creating uncertainty that can hinder economic growth. We saw this occur with the “stagflation” of the 1970s – high inflation with low economic growth.

- Some companies may have rising input costs (like wages and raw materials) but limited ability to pass those costs on to purchasers, resulting in lowered corporate profits in some sectors of the economy.

What is desirable is to have just the right amount of inflation, which the Fed has determined is 2%. More or less than that can be problematic – so the 7% inflation reported in December is troubling.

What Will Inflation be in 2022?

During most of 2021 Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said inflation would be transitory because it resulted mainly from supply chain and labor disruptions due to Covid, which should be temporary. Since he first predicted inflation would be transitory in April 2021, CPI has jumped from a 4.2% annual rate to 7%. Towards the end of 2021, Chairman Powell has changed his tune and has signaled that the Fed is taking the possibility of persistent (meaning non-transitory) inflation more seriously. As a result, the market is now expecting four interest rate hikes in 2022.

We shouldn’t judge Chairman Powell and the experts at the Fed too harshly for not predicting that inflation would continue to be a problem. Economists don’t wholly understand inflation, and their theories about what causes inflation and even how to best measure it are the subject of debate. The New York Times reported a recent example of this in an article titled “Nobody Really Knows How the Economy Works. A Fed Paper Is the Latest Sign.” The article explained that it is economics orthodoxy that expectations about inflation are a key driver of inflation. That means if people expect higher inflation, they’ll behave in a manner that creates inflation. But a recent Federal Reserve research paper blows this accepted theory apart. The research found no evidence that inflation expectations drive future inflation levels. The first sentence of the Fed paper states: “Mainstream economics is replete with ideas that ‘everyone knows’ to be true, but that is actually arrant nonsense.”

Economists don’t wholly understand inflation, and their theories about what causes inflation and even how to best measure it are the subject of debate.

It is notoriously difficult to predict what future inflation will be. Inflation in 2022 will be affected, among other things, by the course the pandemic takes, the pace at which supply chain problems heal, whether Congress passes additional economic stimulus, and, of course, how the Fed handles monetary policy. In short, too many variables to have a clear outlook on what path inflation will take. The spike inflation we’ve experienced may be transitory or more of a persistent problem. As of January 2022, we just don’t know.

What Investors Should Do

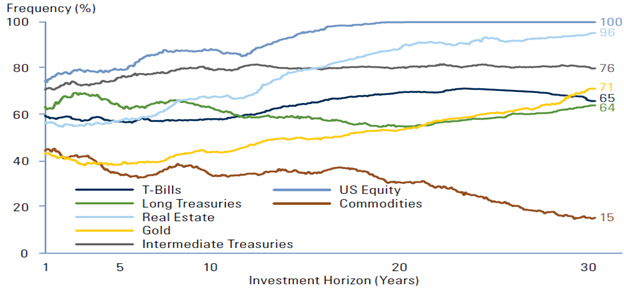

How can investors address the prospect of higher inflation within an investment portfolio? History shows that cornerstone portfolio building blocks have outperformed inflation over time. Looking at the rolling returns of core equities and fixed income over various periods shows that both asset classes have provided a return above inflation most of the time, and the success rate generally improved as the time horizon increased.

Frequency (%) of outperforming inflation over rolling time frames

Key takeaways from the above chart include:

- There are no assets on the graph that are certain inflation hedges over the short term. So, shifting portfolios towards gold or commodities might not be effective.

- Over the long term, equities and real estate provide solid protection against inflation, even though they don’t always keep up with inflation during the short term. A recent report from Goldman Sachs agrees and concludes that equities offer the best chance of outperforming inflation.

- Fixed income (represented by long treasuries and T-bills) doesn’t do as bad as you might think. While rising rates that typically accompany inflation are harmful to the price of bonds, over the longer-term higher rates increase bond returns.

When it comes to hedging inflation, a confounding factor is that different types of investments react differently depending on what is causing inflation. For example, demand-pull inflation may increase company profitability in some sectors resulting in strong equity performance, while cost-push inflation may be bad for corporate profits. Commodities are often cited as a good inflation hedge, but their strong performance during the bout of inflation in 2006-2008 and in the 1970s might be because the main cause of inflation in both periods was a supply-side shock due to a spike in commodity prices. While increasing commodity and oil prices are a factor currently, they aren’t the only driver of current inflation.

Combining that difficulty with how hard it is to predict future inflation, we recommend that investors don’t panic over inflation. If you have a well-diversified portfolio heavy on equities, your portfolio should do well over your time horizon, even if it suffers in the short term. Incorporating allocations to traditional inflation hedge assets introduces additional challenges such as when you should unwind/sell those hedge assets and concern that they may not be effective against inflation this time around. Rather than configuring a portfolio to address a single economic variable, maintaining a long-term strategic allocation built to withstand multiple variables may be the best course of action. This may seem like boring advice, but consistent with Warren Buffett’s admonishment that when it comes to investing, “much success can be attributed to inactivity. Most investors cannot resist the temptation to constantly buy and sell.”

[1] Robert J. Shiller, “Why Do People Dislike Inflation?” in the book “Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy”, Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer 1997 University of Chicago Press.